As usual, the last few months of the year are a time when I frantically try to catch up on movie releases, especially with the late-year influx of (ostensibly) great films that presage the beginning of awards season. Below are my thoughts on a few new(ish) releases by Wes Anderson, Takashi Yamazaki, and Pablo Larraín. Several of these were Netflix releases, and I confess to a knee-jerk resistance to many of the films that corporate behemoth distributes. (Unfair? Probably. But Netflix’s patronage is a big reason why I disliked last year’s Glass Onion, a movie that pats itself on the back for being politically disruptive even though it’s produced by one of the biggest media companies on the planet.) There’s much to offer in the films below, but also a great deal that feels missing or unrealized; hopefully some of the year’s impending releases are a bit more successful in realizing their potential.

It almost goes without saying now that Wes Anderson is one of the best visual stylists in movies today; the aesthetic precision of his works is always impressive, even if the movies around such formal meticulousness leave something wanting. This year’s Asteroid City, for example, feels like strained self-repetition, and the theme about the rift between the pains of reality and the magic of artifice mostly goes to show how out-of-touch Anderson is with the average person’s everyday life. I liked The French Dispatch a bit more—as an ode to French culture, its narrative looseness and thematic flimsiness seem almost intentional—but it would still be nice if the movie had anything to say about the publishing industry, high art, political revolution, or any of its other purported subjects. The last Anderson movie I really loved was The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), which presented one of the few instances in which Anderson peeks through the windows of his dollhouse to witness (and comment upon) the difficulties of the human experience.

At first glance, Anderson would seem to be a perfect match for the stories of Roald Dahl, the fantasist who’s spellbound audiences for generations with his dark and whimsical visions. Generally, I think Dahl balances a kind of insular imagination with effective terror and pessimism more ably than Anderson; stories like The Witches and James and the Giant Peach hint at intense emotions while clearly shrugging off expectations of realism. Anderson first adapted Dahl in 2009’s Fantastic Mr. Fox (which was also Anderson’s first fully animated feature). Now, Anderson has written and directed a quartet of short films adapted from Dahl’s work, thanks to the backing of Netflix (who acquired the Roald Dahl Story Company in 2021 for $686 million; obscene wealth has its privileges).

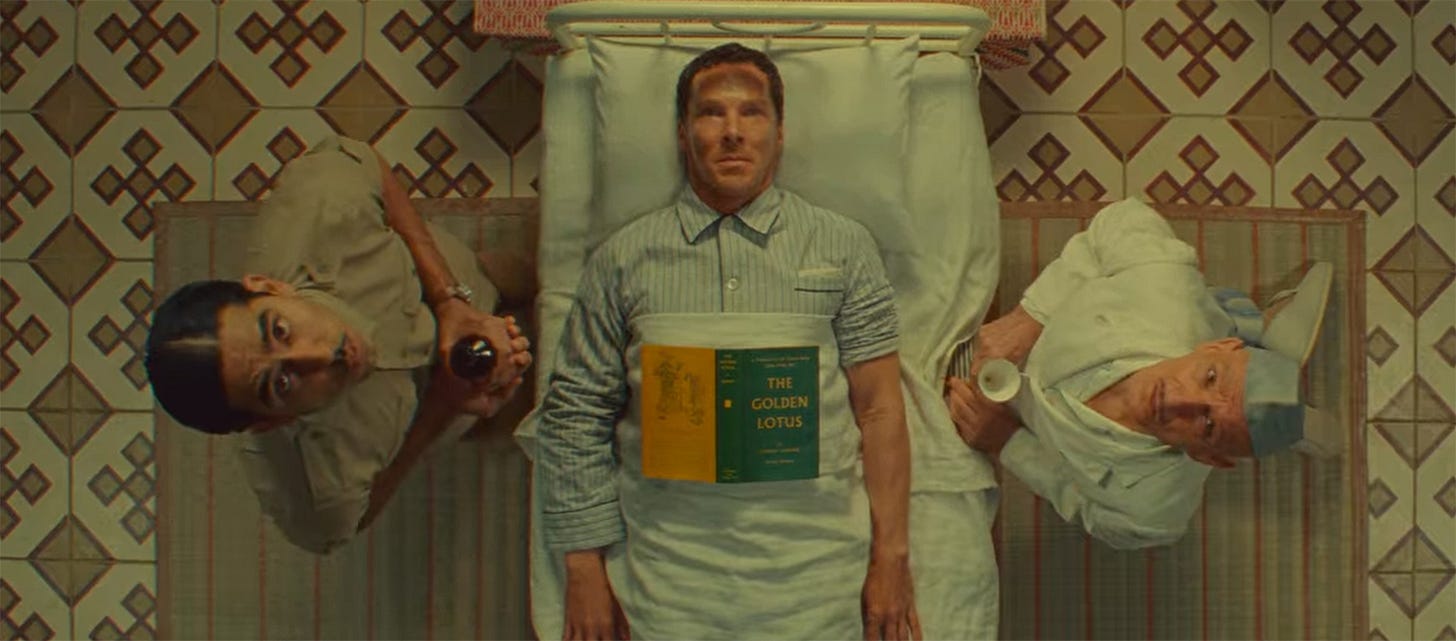

Maybe not surprisingly, my least favorite of the new shorts is the longest one: The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, which runs about 39 minutes. Using his now-customary frame narratives, embedded stories, and experimentation with cinematic, literary, and theatrical storytelling, Anderson relates the tale of the titular bachelor (Benedict Cumberbatch), who became filthy rich thanks to an inheritance and spends his days indulging his gambling habits. He learns of an Indian yogi named Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley) who gained the ability to see without using his eyes. Over the course of several years, Sugar practices his yoga meditation using Khan’s teachings and gains the ability to read playing cards without actually seeing them, allowing him to become even wealthier. Almost inevitably, he comes to realize the dullness of this practice—now that winning is ensured, gambling has lost its thrill for him—and devotes his later years to distributing his exorbitant riches to the needy.

Such a sentimental story is a bit more convincing presented through Dahl’s droll prose than through Anderson’s extravagant stylistics; the entire short has the feeling of containing less than meets the eye. The experimentation with storytelling styles—demonstrated here by characters’ propensity to narrate actions onscreen directly to the camera, even interjecting “he said” or “I said” at rapid-fire pace—is amusing but seemingly pointless, though extradiegetic scenes in which we witness Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) practicing his craft at his writing table provide poignant tributes to the author. Finally, the short continues Anderson’s oft-questionable Asian exoticism, most clearly a problem in Isle of Dogs but also present in The Darjeeling Limited: Kingsley’s Indian ancestry only partially obviates this problem, as Anderson clearly isn’t very interested in Eastern religions or in any of the Indian characters who act as colorful extras in the film.

The other shorts in this quartet (all of which are around 17 minutes) fare better. My favorite is Poison, which offers a welcome dose of thematic subtext. Cumberbatch appears again as British soldier Harry Pope, residing in India during the period of British occupation. One night, Harry discovers a venomous snake called a krait curled, sleeping, on his stomach, and fetches his Indian friend, Timber Woods (Dev Patel), to rescue him before he’s fatally bitten. Timber, in turn, calls an Indian doctor named Ganderbai (Kingsley), who races to Pope’s side in his time of need. This short features some of the most stunning compositions in the quartet (courtesy of D.P. Robert Yeoman)—including some overhead shots that acrobatically follow characters from one room to the next throughout Pope’s house—and ends with an implicit denunciation of colonialism and the bitter sense of paternalism it imbues in the colonizer. I’d go so far as to call Poison one of my favorite Anderson films to date, as thought-provoking as it is gorgeous to look at.

The other two shorts are equally sumptuous but not quite as interesting. The Rat Catcher stars Fiennes as the eponymous character, who’s become overwhelmingly ratlike himself as he hunts vermin throughout the English countryside. This short veers toward horror in its final moments, offering harshly lit extreme angles that might be seen in a Hammer horror production; it’s something of a one-joke film, but extremely well-executed. Finally, The Swan tells the story of two young, violent bullies who terrorize a young bird-lover (played as an adult by Rupert Friend, who also provides nonstop onscreen narration). Soaked in amber and golden hues, this is a beautifully shot work that conveys its anti-bullying message in non-preachy, magical-realist ways, though once again, Anderson’s insistence on infusing literary and cinematic narration detracts from the piece rather than strengthening it.

I like all four of these shorts better than Asteroid City, with Poison approaching true greatness. And yet, the same flaws that aggravate me in most of Anderson’s recent work still make themselves apparent. How I wish Anderson would occasionally direct a screenplay written by someone else; he’s an auteur who offers solid evidence that, sometimes, a unique artist being forced to rein himself in instead of enjoying complete freedom to indulge himself can be a good thing.

Just in time for the seventieth anniversary of the original Godzilla, Toho Studios has released the newest installment in the franchise, Godzilla Minus One. Written and directed by Takashi Yamazaki (who I have to admit is unknown to me, though he’s made a number of successful Japanese blockbusters), the newest film is in fact a prequel, taking place before the events of Ishiro Honda’s 1954 film. In the last days of World War II, a kamikaze pilot named Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) abandons his duty—life is too precious for him to sacrifice in the name of nationalism and war—and winds up on Odo Island, where the ferocious Godzilla soon appears, killing an entire squad of mechanics. Years later, Shikishima has the chance to redeem himself (in his own eyes and his countrymen’s) when Godzilla reappears and lays waste to Shikishima’s hometown of Ginza.

There’s a lot to love here, especially for kaiju enthusiasts: fantastic CGI that emulates the original “suitmation” look but is still convincing (and terrifying); thematic commentary on Japanese culture’s emphasis on duty and sacrifice, even to the detriment of family or personal happiness; a bombastic musical score that infuses the well-known strains of Akira Ifukube’s original soundtracks at ideal moments.

But I’m surprised by the film’s glowingly enthusiastic response, which has many commentators calling this the greatest Godzilla film ever. For me, that title will probably always belong to the Honda original, which infused audacious political commentary with genre thrills in ways that few Japanese movies had done before. Second best for me would be the 2016 reboot Shin Godzilla by Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi, which employs a bewildering visual style, kinetic fast pace, and darkly funny themes about bureaucratic ineptness to reinvent the franchise. (The makers of Godzilla Minus One, in fact, decided to make a historical period piece in order to avoid comparison to the present-day Shin Godzilla, which I would say is the superior film in practically every way.) I even prefer a few other kaiju films from Toho’s 1960s-1990s period to Godzilla Minus One, such as the exhilarating Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964) and the wildly original Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). (Maybe this is betraying my love of Ghidorah a bit too blatantly.)

In any case, I think Godzilla Minus One does have several significant flaws. The final thirty minutes revel in cliches that any audience could see coming from the very start, and the film’s desire to be meaningful and profound makes it somewhat draggy and painfully sentimental. The cinematography by Kozo Shibasaki is also a bit too flat and muddy for my tastes: every sky in the movie looks gray and overcast, and the vast expanse of ocean looks surprisingly dull. (I’ll take the blatant artificiality of Toho’s old studio-shot movies any day.) Fans of Godzilla and kaiju movies should absolutely see this newest entry; many of them will probably love it (and will most likely lose their shit when Ifukube’s familiar score makes its first appearance). Even so, my favorite kaiju film of 2023 is Shin Ultraman (by Shin Godzilla’s co-director, Shinji Higuchi), which came out way back in January and boasts a colorful visual palette, a bizarre and spellbinding story, and a sense of sheer exhilaration that Godzilla Minus One can’t match.

Another Netflix release from 2023 is El Conde, by the Chilean director Pablo Larraín. His filmography to date is one of the most unique in modern cinema: he started with a series of biting satires in his home country (including the clever and stylish No from 2012—my favorite of his films so far) before making a pair of biographical dramas overseas, Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021). In the past, he’s wedded a sense of political outrage with formal majesty and a kind of inscrutable character study. With El Conde, he adds genre experimentation to the mix: the film presents Chile’s notorious military dictator Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell) as a 250-year-old vampire, who started his undead life in France feeding on guillotine-happy revolutionaries before fleeing to South America for “fresh blood.”

El Conde presents sobering truths from Chile’s turbulent recent history—including Pinochet’s orders to kill thousands of Chilean leftists and Communists, his building of exorbitant wealth through a number of sketchy international bank accounts, and the United States’ role in ushering Pinochet into power and sustaining his despotic rule—while indulging in the most well-known aspects of vampire lore. This version of Pinochet flies over Santiago at night with his military cape fluttering in the wind; he rips beating hearts out of his victims’ bodies and purees them in a blender (the younger and more innocent the hearts, the better). But I wish the movie did more with its vampiric imagery; the metaphor of tyrants like Pinochet and Margaret Thatcher (who makes an unexpected appearance) literally feeding off the blood of their constituents starts fairly obvious and grows even more tiresome. El Conde is more successful when it discusses tangential subjects—like the allure of sin and corruption and how family ties can only deepen amorality—in a more dialogic manner.

Shot in silky black-and-white by Ed Lachman, El Conde looks marvelous and thankfully has a grim sense of humor about itself. (There’s an amusing scene in which an old, fatigued Pinochet tries to go out “hunting” but can barely manage to feed on an equally old and immobile victim, whose blood is almost worthless.) But in the end, it’s not clear what the use of the vampire mythology is supposed to be, aside from making a vague and obvious point about how political leaders prey on their subjects. The story becomes even more muddled and unconvincing with the arrival of a French nun (Paula Luchsinger) who happens to be a skilled accountant, leading to her being hired to resolve the Pinochet family’s finances; the amount of contrivance that goes into this character and her involvement in the primary story saps the end of the film of its power. Normally, combining political commentary with genre excitement is right in my sweet spot, but El Conde makes tepid use of its horror-movie influences and fails to make much of an impact. Maybe Pinochet is one of the few cases in which a somewhat journalistic approach (such as in the Battle of Chile documentaries by Patricio Guzmán) does more justice to the horror of what really happened than the phantasmagoric approach that Larraín employs in El Conde.