My Favorite Directors

A pantheon of filmmakers who define my cinematic tastes.

Recently, a friend asked me who my favorite director of all time is, and although a small list of filmmakers came to mind, I realized I couldn’t easily answer that question. While that’s probably not a bad thing—how can you choose from so many greats?!—it inspired me to come up with a shortlist of my favorites.

The list of twenty filmmakers below, with each director represented by my favorite film of theirs, reveals my cinematic biases, for better or worse: European “art movies,” Hollywood greats, Asian cinema, etc. And while some of the all-time titans are missing from this list (Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, Welles, etc.), I’d rather err on the side of distinctness than conform to the list of great auteurs so common in cinephile circles.

1. Jacques Tati

Tati only made six features throughout his career, but several of them rank among the greatest movies of the twentieth century. He started as a mime and circus performer before becoming a filmmaker through a partnership with producer Fred Orain. Four of his six features follow the exploits of Monsieur Hulot, a tall, bumbling, sweet-natured clown who seems perpetually out of place in the modern age.

In my opinion, no filmmaker took inspiration from silent comedy to deconstruct modernity as boldly as Tati. What I admire most about my favorite filmmakers is their refusal to be easily categorized, existing on the fringes of numerous genres and styles. That’s exhilaratingly true of Tati. He frequently pays homage to silent cinema, but sound design is of paramount importance in his movies. His formal style is precise and endlessly rich—nowhere more so than in Playtime (1967), for which Tati and his crew built a miniature version of Paris that almost bankrupted him—but he’s also an ardent humanist, bewitched by the absurdity of human beings. His movies are sad and hilarious, shaggy and immaculate, simple on the surface but inwardly complex.

Playtime is considered his masterpiece, but it’s Mon Oncle (1958) that’s one of my favorite movies; it’s almost as innovative in its style as Playtime, but with an emotional resonance (especially in its deceptively uplifting ending) that overwhelms me every time.

2. Fritz Lang

From the days of German Expressionism to the heights of classical Hollywood (and back again), no one infused fast-paced storytelling with visceral panache as powerfully as Lang. (Except Hitchcock, maybe, who had an ongoing rivalry with Lang early in his career.) A notorious tyrant on the set, Lang epitomized the myth-making potential of cinema—his movies aren’t just epics, they’re legends in motion.

From the 1910s to the early 1930s, Lang made some of the most innovative films of the silent era in Germany, including the haunting Destiny (1921), the supervillain caper Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), the massive Die Nibelungen (1924), and the rollicking Spies (1928), which visualizes the fast-paced technologies of modernity perhaps better than any film ever made. Two films from the early ‘30s, M (1931) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), experimented with sound design in ways that few movies dared to do at the time.

With the rise of Nazism, the half-Jewish Lang emigrated to France and then the United States, where he continued to make formally dazzling masterworks in Hollywood that are unfairly overshadowed by his earlier career in Germany. Fury (1936) passionately decries mob justice, while You Only Live Once (1937) offers a playfully existential crime picture. He made some of the best spy films of the World War II era in Hollywood (including 1944’s Ministry of Fear), while Scarlet Street (1945) and The Big Heat (1953) offer two of the darkest visions from Hollywood's Golden Age.

The horrors of the twentieth century—fascism, war, technology, capitalism—become sinister presences in Lang’s films, but there are also more timeless evils to contend with: lust, jealousy, hubris, self-destruction. My favorite Lang picture is his early-sound masterpiece The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), which is the most terrifying and prophetic vision of the “empire of crime” that would soon emerge in Germany.

3. Abbas Kiarostami

Like Jacques Tati, Abbas Kiarostami is at once a densely cerebral and painfully sincere filmmaker. After starting as a painter and advertising designer in Tehran, Kiarostami founded the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, which offered a way for film directors to skirt censorship constraints and deliver sociopolitical commentary. (The films made there weren’t as strictly supervised by the government because they were ostensibly “kids’ movies.”)

While Kiarostami’s early films have a neorealistic vibe, he would eventually complicate this approach by injecting elements of self-reflexivity, formal deconstruction, and philosophical and spiritual themes. The first part of his so-called Koker trilogy, Where Is the Friend's House? (1987), is a wondrous story of the moral awakening of a child; it’s one of the only times a movie’s finale has made me cry tears of joy. The rest of Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy (And Life Goes On from 1992 and Through the Olive Trees from 1994) is almost as overpowering and arguably even richer thematically.

In the 1990s, Kiarostami made dazzling nuggets like Close-Up (1990), Taste of Cherry (1997), and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999). Taste of Cherry especially is hypnotic and fascinating in its slow pace and its attention toward modern Iran’s vibrant and diverse (if occasionally contentious) communities. Later, in the 2000s, films like Ten (2002) and Shirin (2008) blurred the line between reality and fiction in ways only Kiarostami could achieve.

This output would be enough to solidify the legend of any filmmaker, but my favorite Kiarostami film came out in 2010: Certified Copy, starring Juliette Binoche and William Shimell. It was Kiarostami’s first European production with a mostly professional cast, but the blend of humanism and ambiguity couldn’t be more Kiarostami-like. Certified Copy is my favorite example of what I would call casual surrealism: only gradually do the film’s riddles and absurdities sneak up on you, so by the end, you still don’t know who the characters are and why they behave the way they do—mirroring the mercurial nature of any individual.

4. Wim Wenders

My favorite director to emerge from the New German Cinema is Wenders, whose movies often revolve around the fruitless search for existential meaning and the fleeting nature of human connection. That sounds like dire subject matter, but his movies are frequently funny and ravishingly beautiful, thanks partially to his collaboration with cinematographer Robby Müller.

What I love most of all is the way Wenders (and Müller) film geographic spaces, as if they’re trying to excavate the heart and soul of a place simply by looking hard enough. Whether it’s New York in Alice in the Cities (1974), the American Southwest in Paris, Texas (1984), Berlin in Wings of Desire (1987), or Tokyo in Notebook on Cities and Clothes (1989) and Perfect Days (2024), Wenders’s films envision a global community at once connected and separated by the distinct cultures on display.

His movies also exude a cinephilic energy (like The American Friend, which features Nicholas Ray and Samuel Fuller in cameos) and revolutionize documentary form—particularly with Pina (2012), my favorite-ever use of 3D. But the relatively early Alice in the Cities is still my favorite by him, a profound and melancholy portrayal of an unlikely surrogate father-daughter relationship.

5. Michelangelo Antonioni

A theme is becoming apparent: alienation in the mid-twentieth century, evoked through visual beauty, a kind of hard-edged sympathy, and cryptic themes that ask the audience to do most of the legwork. Antonioni epitomizes that kind of cinema: his name is practically synonymous with alienation on film.

While he started creating his unique style in the 1950s, it was L'Avventura (1960) that put him on the map—particularly in the way the narrative sets up a mystery that’s never solved, putting the emphasis instead on the deeper existential crises of the characters. Along with Citizen Kane and Journey to Italy, L'Avventura introduced a new kind of modernist language in cinema, an ambiguous style that Antonioni would perfect throughout his career in movies like La Notte (1961), Red Desert (1964), and The Passenger (1975).

His movies could be self-indulgent to the point of parody: one of his most celebrated films, Blow-Up (1966), might be my least favorite, and I find Zabriskie Point (1970) similarly phony, despite its stunning ending. But even then, you have to admire a director so committed to his philosophical inquiry that he’s not afraid to appear pedantic and strident.

My favorite thing about Antonioni is the intersection of architecture and cinema: in movies like L’Eclisse, my personal favorite, the hulking, emotionless spaces of Rome visualize the hollow mindstates of the characters, with the silky black-and-white cinematography creating a beautiful but desolate aesthetic. It doesn’t hurt that Antonioni often worked with actors who have a phenomenal presence—particularly Monica Vitti, my favorite actress of all time.

6. Louis Feuillade

In the silent era, the Lumière Brothers and Georges Méliès established a fork in the road for cinema: realism on one hand, fantasy on the other, obviously with a lot of overlap and weaving back and forth. But another presence in silent cinema introduced an equally influential pivot: Louis Feuillade, whose crime serials in the 1910s exist on the border of surrealism and reality, narrative and experimentation, the mainstream and the avant-garde. Whenever I think of genre-straddling filmmakers like Cronenberg and Chabrol, I see Feuillade as their spiritual forebear.

In the midst of the Great War’s chaos in the 1910s, Feuillade’s serials evoked the violence and paranoia of modern urban spaces. Several installments of the Fantômas serial (1913-14) introduced uncanny horror to the cops-and-robbers potboilers so popular at the time. The effect was even more startling in the ten-episode Les Vampires (1915-16), in which trains, telegrams, claustrophobic interiors, and other aspects of modernity provide an avenue for all kinds of supervillainy. Feuillade tried to appease his critics by making the villains less glamorous in Judex (1916), but he still couldn't resist reveling in explosive anarchism.

These serials are a relatively small fraction of Feuillade’s output: he made over 600 movies from 1906 to 1924. But the impact they would have on a peculiar blend of commercial/surrealist filmmaking survives to this day. I consider Les Vampires my favorite “film” (though it’s actually a serial released over the span of two years), and Feuillade is a foundational artist for me, encapsulating everything I find so bizarre and unexpected about the movies I love.

7. Kelly Reichardt

Aside from Wim Wenders, Reichardt is my favorite living filmmaker, a true maverick in modern American cinema. After her debut feature River of Grass (1994) and several short films, her 2006 picture Old Joy might be seen as her first characteristic work, providing in-depth character study and a (deceptively) minimalist aesthetic. Her follow-up, Wendy and Lucy (2008), is one of my favorites of the twenty-first century so far, wielding the framework of neorealism to comment on the extent to which poverty impacts our relationships with those we love.

Since then, Reichardt has spun her naturalistic style in fascinating directions. Meek’s Cutoff (2010) is a hyperrealistic Western that journeys to the edge of death. Certain Women (2016) is another neo-Western that rigorously explores class and gender dynamics. Night Moves (2013) even veers close to a political thriller. Every time she makes a movie, you get the sense that she’s trying to surprise both the audience and herself—resulting in some of the most exciting movies of the last twenty years.

8. Vincente Minnelli

Many Hollywood directors were able to make great art in the classical studio system, but Minnelli is my personal favorite (aside from Lang). His ingenuity was present from his directorial debut, The Cabin in the Sky (1943), which features an all-Black cast comprised of Broadway and musical stars like Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Ethel Waters.

I generally prefer Minnelli’s musicals, like Meet Me in St. Louis (1943) and An American in Paris (1951), which are both light and entertaining on the surface but offer strengths that transcend the genre: a wistful look at a family and an era in flux in Meet Me in St. Louis; a sympathetic look at a struggling artist in An American in Paris (which did more for Franco-American relations than anything since the Statue of Liberty). One of Minnelli’s best non-musical pictures is Some Came Running (1958), a complex, heartbreaking, stunningly gorgeous look at the rotten underbelly of small-town America after World War II.

Minnelli had an especially fruitful collaboration with Judy Garland, whom Minnelli married in 1945. The same year, they made one of my favorite movies: The Clock, which is an airy romance on the surface but confronts time and mortality in the wake of the war.

9. Jean-Pierre Melville

No disrespect to Michael Mann fans, but Melville is the greatest crime director of all time. During World War II, the Jewish Melville (who was born Jean-Pierre Grumbach) served in the French Resistance and adopted his new surname in honor of his favorite author, Herman Melville. After the war, he started his own studio in Paris, rising to prominence as one of France’s first true independent filmmakers.

Stylish, austere, and incomparably cool, Melville’s crime pictures are definitely entertaining as cops-and-robbers potboilers, but they hide an existential despair at their core: whether criminals or lawmen, these characters simply stumble into their vocation and play it out until death inevitably comes. But there’s honor and fleeting connection to be found within the apparent meaninglessness. Films like Le Samourai (1967) and Le Cercle Rouge (1970—my personal favorite) were among the first to posit the idea that cops and crooks are essentially the same—they just happened to end up on opposite sides of the law.

Though he’s best known for his crime movies, Melville occasionally ventured into more personal or philosophical territory, as in the semi-autobiographical Army of Shadows (1969) and the fascinatingly dense Leon Morin, Priest (1961).

10. Ernst Lubitsch

No other director in film history is so synonymous with sparkling wit, glamor, and elegance. Indeed, the “Lubitsch touch” eventually became a catchphrase for a brand of graceful comedy that radiates effortlessly from the screen.

Although his German silent films didn’t yet master the humor and style that he’d become known for, they do hint at Lubitsch’s playful innovations—particularly I Don't Want to Be a Man (1918), which offers witty gender-bending comedy 41 years before Some Like It Hot. (This might not be a coincidence: Lubitsch was also one of Billy Wilder’s idols.)

After leaving for Hollywood in 1922, Lubitsch directed a series of Hollywood silents that saw him experimenting with visual style (for example, through highly mobile camerawork and sets that echoed German Expressionism). These early classics include The Marriage Circle (1924) and Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

The advent of sound allowed Lubitsch to refine his singular style, creating masterful early musicals like The Love Parade (1929), Monte Carlo (1930), and The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), which played with sound design (and offered aural punchlines) that few other sound movies attempted at the time. Lubitsch’s mastery would continue throughout his career, as he helmed great comedies like Design for Living (1933), The Shop Around the Corner (1940), and Heaven Can Wait (1943).

What I love most about Lubitsch is the combination of bawdiness and sophistication (his 1930s comedies are among the sexiest ever made) and the fact that his movies are more personal than they appear at first glance. This is especially true of The Shop Around the Corner, which is set in a shop that might have been similar to the one Ernst’s father owned in Berlin when the director was a child. My favorite Lubitsch film, though, is Trouble in Paradise (1932), one of the funniest and most glimmering Hollywood comedies of the early sound period. While you can point out some of the specific signs of formal innovation in that film (for example, the montages that speed the story along through composition and editing alone), there’s something indefinable about the gracefulness of Trouble in Paradise—it can simply be summed up as the Lubitsch touch.

11. Claire Denis

A poet who defies expectation at every turn, Claire Denis is one of modern cinema’s true iconoclasts. After growing up in African nations like Senegal, Cameroon, and Burkina Faso (her father was a civil worker for France, though he supported these nations’ independence), Denis served as assistant director for such filmmakers as Jacques Rivette, Costa-Gavras, and Wim Wenders. This unique background led to a genre-defying, unpredictable style right from the start, in early movies like Chocolat (1988), I Can’t Sleep (1994), and Nénette et Boni (1996).

In 1999 came Denis’s most celebrated film, Beau Travail, a stunningly gorgeous and atmospheric adaptation of Melville’s “Billy Budd” shot in Djibouti. She’s made some of the most striking and indefinable movies of the 21st century ever since, including the macabre Trouble Every Day (2001), the Ozu-inspired 35 Shots of Rum (2008), and the abrasive but powerful High Life (2018). Impressively prolific, Denis maintains an astonishing level of creativity and richness throughout her work—the release of a new Denis film is always cause for celebration.

My favorite of hers (and one of my favorite movies) is L’Intrus (2004), which might be the most sensuous and overwhelming piece of cinematic poetry in the last thirty years. Within its cryptic, impressionistic scenes lies a sense of profound truth regarding the unexpected paths that a human life takes.

12. Nicholas Ray

Another Hollywood director who smuggled subversive themes and a dynamic visual style into the constraints of a studio system. The auteur from La Crosse, Wisconsin had a knack for making tragedy visceral and propulsive (They Live by Night [1948], Bitter Victory [1957]) and using color more expressively than almost any of his Hollywood peers (Rebel Without a Cause [1955], Bigger Than Life [1956]). These movies, along with the camp masterpiece Johnny Guitar (1954), spoke to destructive forces lurking beneath the surface affluence of American life. Not surprisingly, he would become a hero to other directors (including European auteurs like Godard and Wenders) for his ability to make personal art despite the constraints and logistics of large-scale moviemaking. My favorite Ray picture is In a Lonely Place (1950), which boasts my favorite Humphrey Bogart of all time (Ray was also an underrated director of actors); Bogie plays an alcoholic, toxic screenwriter who may or may not have killed a woman, and it’s terrifying how relatable Bogart makes the despicable character.

13. Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

Powell and Pressburger are the only director(s) on this list to have two different movies in my top twenty: Black Narcissus (1947) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946). In reality, Powell did most of the directing work while Pressburger assumed producing and editing duties, with both of them usually working on the scripts together. For several decades, this filmmaking duo was synonymous with British cinema, under the guise of their production company, The Archers. In the two films listed above—as well as in masterpieces like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and The Red Shoes (1948)—Powell and Pressburger combined fantastic visuals (in every sense of the word), droll humor, and a sense of unabashed romanticism to create some of the most magical cinematic visions of all time. Special mention should be made of Powell’s solo project Peeping Tom (1960), one of my favorite (pseudo-)horror movies.

14. F.W. Murnau

No disrespect to the United States, France, or Japan, but together with Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau made Germany the most creatively fertile locale for silent cinema. In the 1920s, Murnau envisioned a liberated formal style that saw little purpose for intertitles: his films are driven by pure visual storytelling. He was masterful at creating images of terror, whether those evils are social (The Last Laugh [1924]) or metaphysical (Nosferatu [1922], Faust [1926]). When Murnau moved to Hollywood in 1926, he responded by making perhaps the greatest American silent movie—Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), which tells a timeless story of love and loss using the most operatic visuals imaginable. His later films, like City Girl (1930) and Tabu (1931), play with sound in ingenious ways, only a few years into the existence of “talkies.” When I think of the most purely cinematic images in history, several Murnau films come to mind: the two lovers blissfully walking through streams of traffic in Sunrise; the titular monster’s shadow lurking on a staircase in Nosferatu; an unmoored camera swinging wildly from the ceiling in The Last Laugh; the list goes on.

15. Jules Dassin

Another American director who breathed unique life into (and eventually escaped) the Hollywood system, Dassin is my second favorite crime director after Melville. His talents were apparent from his first feature for MGM, Nazi Agent (1942), which elicited comparisons to Welles and Hitchcock upon its release. He made several vivid and violent dramas early in his Hollywood career, including Brute Force (1947) and The Naked City (1948), the latter of which was recut against Dassin’s wishes. In the late 1940s, Dassin—a longtime Communist—was in danger of being blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee, so the director was rushed to England, where he made Night and the City (1950) for 20th Century Fox. This is my favorite Dassin film and one of the best “city movies” ever made—a romantic but heartbreaking ode to dreamers who try to find success and glamor in the big city, featuring an excellent Richard Widmark performance.

In exile, Dassin made the French Rififi (1955)—a tense and influential crime caper —and several movies with his second wife, Melina Mercouri. My second favorite Dassin picture is Uptight (1968), which the director made after he returned to the U.S. from France; written by Ruby Dee, Uptight is an adaptation of John Ford’s The Informer set in the context of the Black Power struggle of the ‘60s, offering a fascinating intersection of classical Hollywood cinema, racial politics, and the classical conventions of the crime genre.

16. Jacques Tourneur

Has any director made such masterful use of limited resources as Jacques Tourneur? The French-American filmmaker had a particularly successful collaboration with producer Val Lewton at RKO; this partnership led to such atmospheric, low-budget gems as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943). The latter is one of the most remarkable movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age, a mini-masterpiece (it’s barely more than an hour) that touches on the devastating effects of colonialism. Tourneur mastered other genres, too, like film noir (Out of the Past, 1947) and Westerns (Stars in My Crown, 1950). His movies are a testament to the liberating aspects of working under the radar on B-list projects, particularly in the horror genre.

17. Jia Zhangke

The Chinese director Jia Zhangke makes sprawling, complicated films that somehow seem to encapsulate the sense of precarity, disenfranchisement, and alienation that define the modern world—and his home country in particular. His earliest underground films, made without the sanction of China’s official film industry, adopt a distanced approach in the manner of Hou Hsiao-hsien to comment on the waywardness of young people at the turn of the 21st century, with 2000’s Platform being a particular highlight. His scope broadened with The World (2004), which offers a playful but ultimately bleak commentary on the nature of duplication and artificiality in a technology-driven age. He’s made some of the most beautiful and haunting films of the 21st century, including Still Life (2006) and A Touch of Sin (2013). Jia inherits Antonioni’s legacy of defining modern alienation, but with a dry sense of humor reminiscent of Jim Jarmusch. My favorite by Jia to date is Ash Is Purest White (2018), a jarring, ambitious portrayal of late capitalism and shifting gender dynamics in modern China.

18. Kenji Mizoguchi

Kurosawa and Ozu deserve their spots in the pantheon of great filmmakers, but my favorite Japanese director from the mid-20th century is Mizoguchi, the master of the long take. Starting in the 1930s, with films like Osaka Elegy (1936) and The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Mizoguchi told stories that laid bare the plight of women in Japanese society, all while perfecting his “one-scene-one-shot” style in which the camera gracefully tracks around the action, subtly shifting perspective. His feminist perspective was likely influenced by the fact that his own sister was put up for adoption (and likely became a geisha) early in Kenji’s youth. For me, Mizoguchi’s masterpiece is Ugetsu (1954), a haunting and elegiac ghost story about the dire impacts of poverty and the “ghosts” of lost love that haunt us throughout our lives.

19. Joseph H. Lewis

Like Tourneur, Lewis’s films demonstrate how working on under-the-radar B-pictures allows for uninhibited formal experimentation and surprisingly subversive themes. Lewis started off with a string of B Westerns in the late 1930s and made training films for the army during World War II. After the war, he made innovative, low-budget pictures in a variety of genres, highlighted by the stunningly beautiful The Big Combo (1955, shot by John Alton) and the gleefully entertaining Terror in a Texas Town (1958, his last film and one of the most socialist American movies ever). The most emblematic Lewis film, though, is 1950’s Gun Crazy, a wildly inventive crime caper that (as the title suggests) says more about our country’s obsession with guns than any number of self-important message movies.

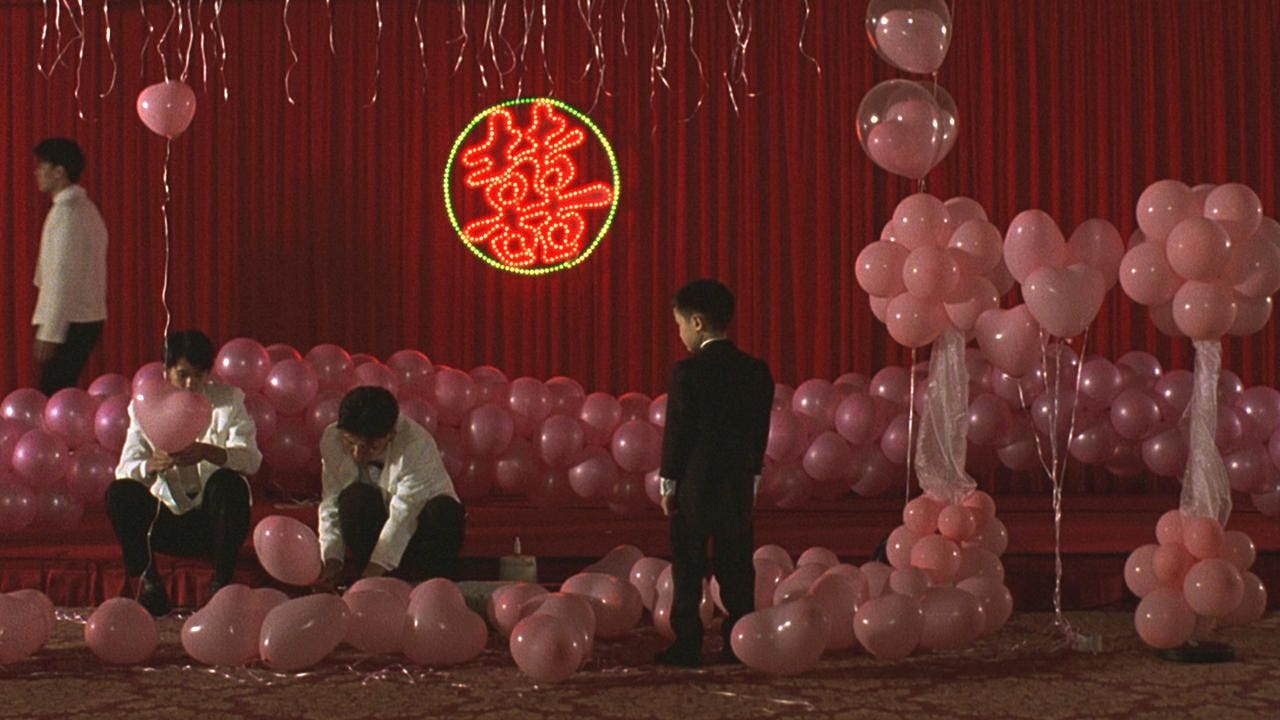

20. Edward Yang

For a relatively small country, Taiwan has provided the world with a staggering number of master directors over the last fifty years: Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang, Ang Lee, etc. My personal favorite is Edward Yang, who (like Antonioni and Jia Zhangke) comments on alienation, late capitalism, and desperate attempts to find human connection. Along with Hou and Tsai, Yang pioneered the Taiwanese New Wave that began in the early ‘80s, offering fractured narratives and an austere visual style comprised of long takes and often static camera setups. Yang’s first two features, That Day, On the Beach (1983) and Taipei Story (1985), observe aimless characters in the big city of Taipei, suffused with a kind of begrudging empathy. One of his most revered films is A Brighter Summer Day (1991), a sprawling look at Taiwan in the mid-20th century as it’s impacted by gang culture, political pressures from mainland China, and the pervasive influence of pop culture. My favorite Yang film, though (and one of my favorite movies), is Yi Yi (2000), a tender but cerebral portrayal of a family in modern Taipei. Jean-Luc Godard once claimed that Au hasard Balthazar is “the world in ninety minutes,” but I think it’s more accurate to say that Yi Yi is the world in three hours.

Runners-Up

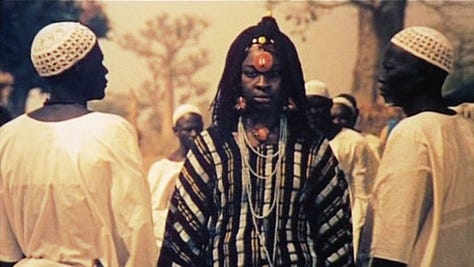

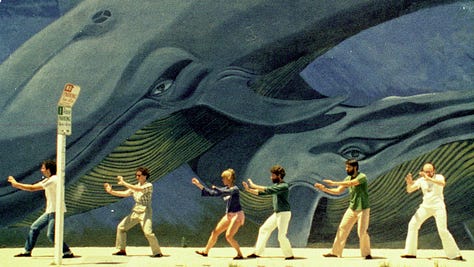

Jafar Panahi (No Bears, 2018); Samuel Fuller (White Dog, 1982); Josef von Sternberg (The Scarlet Empress, 1934); Ousmane Sembène (Ceddo, 1977); Agnès Varda (Mur Murs, 1981); William Wyler (The Little Foxes, 1941); Sergio Leone (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968); Kon Ichikawa (An Actor’s Revenge, 1963); Douglas Sirk (There’s Always Tomorrow, 1956)