In lieu of a best-of-the-year list (which I usually can’t finish until late January anyway, as the last acclaimed movies finally get their theatrical release in Minnesota), below is a rundown of my fifty favorite movies I saw in 2024, regardless of their release date. While there’s something to be said for keeping up with new releases, I usually find lists like this more interesting: they reflect the full scope of cinema’s pleasures across its 130-year history.

1. The Magnificent Ambersons

This rewatch convinced me that Orson Welles’s follow-up to Citizen Kane—one of the most lauded movies of all time—may be even more distinct and shattering than its celebrated predecessor. In adapting Booth Tarkington’s 1918 novel, Welles creates a work that is both richly literary and dazzlingly cinematic, with roving, deep-focus cinematography (by Stanley Cortez) and immersive production design (by Albert D’Agostino) that were truly like nothing else in American cinema at the time. While Citizen Kane is fascinated by the machinery of journalism, The Magnificent Ambersons charts the rise of the automobile and how it reflects shifting class structures in American society. The movie also develops some indelible characters, like the self-obsessed George (Tim Holt) and the woeful Aunt Fanny (Agnes Moorehead). Yes, The Magnificent Ambersons was taken away by RKO and reedited against Welles’s wishes; the studio cut over an hour from the film and tacked on a weak happy ending. Even in compromised form, though, Welles’s second feature is an astounding masterwork of American cinema, not to mention a case study in the competing urges of classical Hollywood: unbounded artistry on the one hand, the demands of money and profit on the other.

2. Céline and Julie Go Boating

This year, I finally got around to seeing Jacques Rivette’s Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974), a quietly surreal spin on Alice in Wonderland that also functions as a meta-commentary on the art of storytelling. The titular friends stumble upon a “house of fiction” in Paris in which a melodramatic storyline plays out ad nauseam—something involving two conniving sisters, a widower, and an endangered child. Céline and Julie soon discover that their visits to the house allow them to alter the embedded story within, mirroring the audience’s ability to impact the meaning and scope of their favorite works of art—lending humanity and a sense of humor to postmodern themes. Along with a sense of magic and freewheeling imagination is a sincere depiction of two close female friends, aided by the fact that actors Dominique Labourier and Juliet Berto were longtime friends in real life. Their rapport is only one of many wondrous things about this bewitching puzzle from Rivette.

3. Some Came Running

Vincente Minnelli is one of my all-time favorite Hollywood directors, and Some Came Running might be his most visually sumptuous and thematically complex works: an eye-popping melodrama that exposes the rotten underbelly of small-town postwar American life. Frank Sinatra plays Dave Hirsch, a bitter, cynical, alcoholic soldier returning from war who finds himself in his hometown of Parkman, Indiana, almost against his will. A love triangle involving him, a pretty schoolteacher (Martha Hyer), and a fun-loving girl who makes terrible decisions (Shirley MacLaine) reveals the town’s violent class distinctions. Meanwhile, Dave’s friendship with a gambler named Bama (Dean Martin) brings out his worst tendencies for drinking, womanizing, and self-loathing. The 1950s might be the richest period of American cinema because of movies like this: it benefits from all the resources of Hollywood studios and the best craftsmen in the world but tackles sensitive, provocative subject matter (postwar despair, destructive masculinity) through allusion and metaphor (the better to get around the Production Code’s censorship). It all builds to an unforgettable nightmare vision of pleasure and ruin run rampant on the streets of Americana.

4. Parade

The final feature from Jacques Tati (my favorite director) is often dismissed even by fans of the filmmaker’s work: produced for Swedish television, it’s ostensibly a filmed performance by Stockholm’s Circus Theater, though Tati throws in some of his early circus acts (before he was a director, Tati was a mime) and staged vignettes that incorporate members of the audience. In this way, Parade and Céline and Julie share a theme about the primacy of the audience over the media they experience. Maybe another reason Parade is discounted by some Tati fans is because it’s shot using a combination of 35mm, 16mm, and digital video, so it lacks the opulence of something like Playtime (1967); but what it gains instead is an utterly unique style that’s as aesthetically unpredictable as the circus acts on display. What I love so much about Tati is the contradictory aspects that combine to create something one-of-a-kind—he’s playful and precise, humane and cerebral, hilarious and melancholy—and those wide-ranging traits are on full display in Parade.

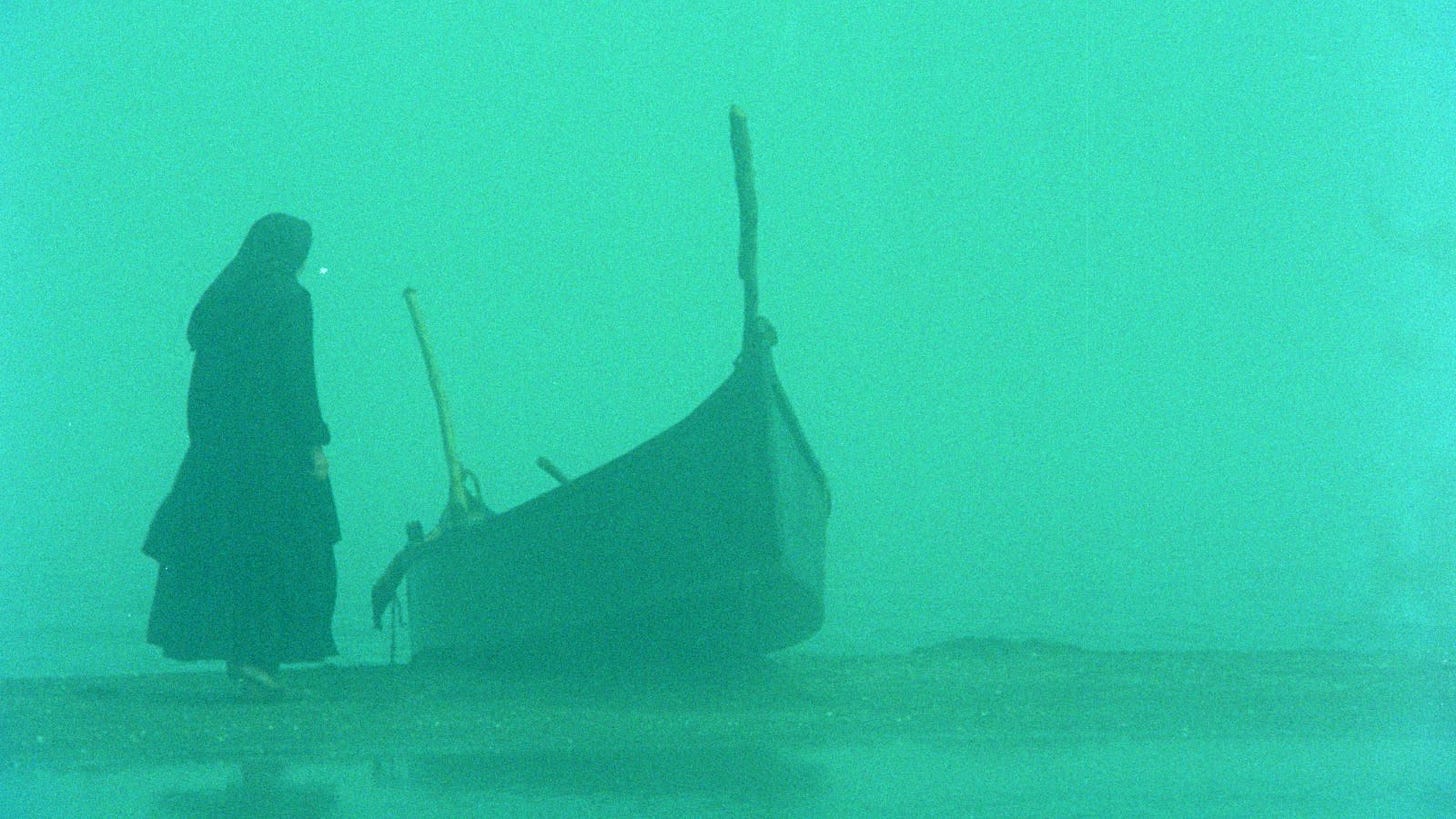

5. The Stranger and the Fog

This lost classic of the Iranian New Wave premiered in 1974 in its home country, received a few scattered screenings, then was banned in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, after which it essentially went missing for decades. One of the positive stories of 2024 was the film’s restoration by the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna in honor of the movie’s fiftieth anniversary, which brought this cryptic, magisterial film back to light. Writer-director Bahram Beyzai turns a simple tale—a stranger washes up on a northern Iranian shore, where he’s guardedly accepted by a small coastal community though he continues to fear that some unnamed presence is after him—into an allegory for persecution and extremism. The Stranger and the Fog is haunting and ambiguous, with atmospheric camerawork (by three different cinematographers) lending the film an eerie, anxious poetry.

6. Under the Volcano

As much as I admired Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, it can’t hold a candle to John Huston’s Under the Volcano (1984), another story about an expat driven to self-destruction on the streets of Mexico. (In fact, the cover of Malcolm Lowry’s 1947 novel Under the Volcano is glimpsed briefly in Queer.) Albert Finney (at his best) plays British consul Geoffrey Firmin, stationed in Cuernavaca in 1938, on the eve of World War II. Outraged by the barbarism of the modern world and despondent over his wife’s adultery (which his alcoholism partly drove her to), Geoffrey wanders the streets on the Day of the Dead, drinking and bemoaning the political state of affairs and trying to maintain his dwindling faith in humanity. As the description suggests, this is a bleak affair, though Finney interjects some much-needed moments of humor; still, there’s tremendous emotional power in seeing a man driven to ruination in the face of the world’s cruelties, leaving a headlong dive into the abyss as one of the few remaining options. Under the Volcano is as hopeless as another movie that John Huston made in Mexico almost forty years earlier, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; both movies are about foreigners who desperately search for escape in an exotic locale, only to realize that escape is nowhere to be found.

7. Autumn Sonata

Truthfully, Ingmar Bergman has never been my auteur of choice—his films sometimes feel too stagebound and unrelentingly somber, leaving out the small joys and oddities of life—but Autumn Sonata is one of my favorites of his. He finally teamed with that other famous Bergman, Ingrid, in this story of a concert pianist, Charlotte (Bergman), who returns to visit her daughter, Eva (Liv Ullmann), after an absence of seven years. The animosity between mother and daughter resurfaces almost immediately, largely a result of the fact that Charlotte was typically absent when Eva was a child, focusing instead on her artistic career. This narrative surely hit close to home for Ingrid Bergman (who infamously left her family and her career in Hollywood to be with Roberto Rossellini), but also for Ullmann and Ingmar, who had a daughter together. As usual in Bergman’s films, the performers carry a heavy load, making these characters seem like real people instead of symbols of abject misery. But cinematographer Sven Nykvist also deserves much of the credit, crafting a dreamlike, impossibly vivid palette for these stark familial dramas.

8. The Cloud-Capped Star

Ritwik Ghatak’s 1960 melodrama is stunningly gorgeous—its black-and-white footage of Calcutta may leave your jaw hanging open throughout. Specifically, the movie takes place on the outskirts of the city, in a camp for Pakistani refugees during the Partition of Bengal in 1947. One of those refugees, Nita (Supriya Choudhury), tries to go through life with hope and positivity despite her and her family’s dire circumstances, but she’s constantly exploited due to her innate goodness. Only her brother Shankar (Anil Chatterjee) truly understands her, but he’s too busy perfecting his singing to make money or support the family. (Shankar’s beloved songs lead to a number of lovely musical renditions, which are as beautiful as the surrounding scenery.) This may sound like a dire slog—and maybe too similar to Satyajit Ray’s landmark 1955 film Pather Panchali—but The Cloud-Capped Star is its own radiant beast, a sympathetic depiction of people beset by tragedy who nonetheless bravely embrace beauty and optimism.

9. Edvard Munch

I normally don’t like biopics, but that doesn’t seem like an apt label for Peter Watkins’s film about the controversial Norwegian painter. Produced by Norwegian and Swedish television networks, Edvard Munch is as impressionistic as the artworks that its subject created, portraying the fears, traumatic memories, and social subtexts surrounding Munch in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. From a family ravaged by tuberculosis in his early years (forcing Munch to watch several relatives die) to a sexual liberation movement that saw Munch’s lovers cast him callously aside, the painter’s volatile headspace comes alive through fragmented montage editing and intimate camerawork. Somehow, the effect is cinéma vérité as it might have existed in the late 1800s. In its abstractions, Edvard Munch presents a more truthful biography, acknowledging that a human being’s messy, turbulent life can’t be encapsulated by a linear sequence of events.

10. Leave Her to Heaven

Is it a melodrama? A film noir? A psychological thriller? Leave Her to Heaven is all the above and more: a delirious mashup in blazing Technicolor, with a radiant lead performance by the one and only Gene Tierney. She plays a socialite named Ellen Berent, who lures a novelist (Cornel Wilde) into marriage; only then does he realize how obsessively she’ll hold onto everything she loves, even if it means letting a polio-stricken teenager drown or hurling herself down the stairs to abort her fetus. (Amazing they got away with this in 1945 Hollywood!) Berent is a deranged sociopath, but she still (thanks to Tierney) is the most captivating character in the film, which plays with audience identification to leave us rooting for the worst person on the screen. With vivid Technicolor camerawork to match the best of Powell and Pressburger, Leave Her to Heaven is wildly entertaining and one of the most surprising American films of the mid-’40s.

11. Design for Living (Ernst Lubitsch, 1933) — I’ve written about this effervescent pre-Code comedy before, but suffice to say no one balanced sexiness, sophistication, and human compassion as gracefully as Ernst Lubitsch. Miriam Hopkins’s performance might be my favorite from a Hollywood actress in the ‘30s: her character is irresistible, full of life and adhering to her own moral code.

12. The Taste of Things (Tran Anh Hung, 2023) — The most romantic movie ever made? This is the kind of film you don’t just love but fall in love with, abounding in sensory pleasures (the sights, the sounds, the foods you feel you can taste) and a central relationship that crackles with chemistry, thanks in part to the fact that Juliette Binoche and Benoît Magimel were onetime partners—their romance here carries a sense of love, loss, and gratitude.

13. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964) — This was my third rewatch and perhaps the first time I understood the full depth of Demy’s bittersweet musical: the proclamations of desire and loneliness are somewhat banal, but here, even the most ordinary human passions are the stuff of extravagant operettas. The older you get, the more you’ll succumb to the soaring ending, which is full of the stuff that cinematic dreams are made of.

14. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) — Maybe this seems too low for a movie commonly considered one of the best ever made. I’ve always been more partial to other Ozu films, like Late Spring (1949) and I Was Born, But… (1932). Regardless, Ozu’s quiet family drama is simplicity at its most profound, charting the transformations of Japanese society through the lens of a family subject, like all others, to the passage of time.

15. Manhunter (Michael Mann, 1986) — Like most of Mann’s work, Manhunter functions as a study in male strength and vulnerability: adapted from Thomas Harris’s 1981 novel Red Dragon (and thus the first time we see Hannibal “Lecktor” onscreen, here played by Brian Cox), it’s an existential serial killer story in which men are always hunting for something, even if they don’t know what. That’s even true of the central villain here, a killer known as “the Tooth Fairy,” chillingly played by Tom Noonan. Mann often has the ability to turn simple crime narratives into sublime male melodramas, and nowhere is that truer than in Manhunter.

16. My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979) — Gillian Armstrong’s first feature is both delightful and affecting, thanks in large part to Judy Davis’s breakthrough performance. She plays Sybylla, an aspiring writer in rural Australia at the dawn of the 20th century. Sybylla cares little for social niceties or romantic union, obsessed only with becoming an important artist—as she knows she’s destined to become. That goal is thrown into question, though, when she’s courted by a dashing, sensitive man (Sam Neill) who might actually carry the promise of love. My Brilliant Career is so funny and warm-hearted that you don’t realize how moving its depiction of a young woman committed to her art really is until its emotional impact sneaks up on you.

17. Pacifiction (Albert Serra, 2023) — On the island of Tahiti, French government official De Roller (Benoît Magimel) wiles away his days in a kind of purgatory paradise; this world is postcolonial in name only, as the presence of France and other foreign nations is ubiquitous. Embroiled in political plots that start to overwhelm him, all De Roller can do is contemplate his role in sinister global geopolitics. Surreal and urgent in equal measure, Albert Serra’s sparkling Pacifiction is captivatingly ominous.

18. Le Samouraï (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967) — Melville is one of my favorite filmmakers, and Le Samouraï (along with Le Cercle Rouge) is his crowning achievement. Nowhere else is Melville’s crime-steeped existentialism (a huge influence on Michael Mann) more apparent: here, cops and hitmen go about their business with grim resolve, fending off human connection even though it’s impossible to avoid. Incomparably cool and icy cold, Le Samouraï is one of the best crime pictures ever made.

19. Ashes and Diamonds (Andrzej Wajda, 1958) — This Polish classic, set shortly after World War II, follows a former resistance fighter (Zbigniew Cybulski, aka “the Polish James Dean”) who’s tasked with killing a Communist leader. But as he flirts with a beautiful bartender (Ewa Krzyżewska) and sees the ruins of his country lying around him, he begins to doubt the purpose of his mission. With richly symbolic imagery (shot in glimmering black-and-white by Jerzy Wójcik), Ashes and Diamonds laments the ongoing violence of war even during times of “peace,” as men can’t bring themselves to stop killing and hating each other.

20. Bay of Angels (Jacques Demy, 1963) — The second Demy film on this list is a dazzling look at the devastating allure of gambling. Jean (Claude Mann), a young banker with a promising career, joins his friend on a trip to a casino; after meeting a woman named Jackie (Jeanne Moreau) who’s addicted to gambling (and has left her husband and infant son to indulge this thrill), Jean finds himself increasingly unable to resist the compulsion. At times this plays like a precursor to Uncut Gems, depicting the allure of gambling—not so much the money as the constant sense of risk—with clear-eyed sympathy. It’s elevated by Moreau’s towering performance, as she movingly conveys her character’s unavoidable drive toward self-destruction.

21. What’s Up, Doc? (Peter Bogdanovich, 1972) — From Jeanne Moreau to Barbra Streisand, both Bay of Angels and What’s Up, Doc? are defined by their lead actresses. Streisand gives one of my favorite-ever performances as Judy Maxwell, essentially the Katharine Hepburn to Ryan O’Neal’s Cary Grant imitation. Bogdanovich didn’t try to hide the fact that this was his remake of/homage to Bringing Up Baby (1938); what’s remarkable is that What’s Up, Doc? is as good as (better than?) the Hawks classic. The film is consistently laugh-out-loud funny (credit to the team of screenwriters, headed by Buck Henry and Robert Benton), but what I’ll always remember is Streisand’s irresistible, magnetic presence.

22. The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968) — This remarkable oddity from New Hollywood offers yet another hypnotic performance as Burt Lancaster plays Ned Merrill, who’s still handsome and athletic well into his fifties. In affluent Connecticut, Ned decides to “swim home” from his friend’s house by cutting through the swimming pools that dot the landscape all the way to his own elegant home; along the way, he revisits some old flames and regrets, realizing the hollowness of the American Dream he achieved long ago. Sad and sexy, funny and grim, this is a standout from a period when the codes and conventions of classical Hollywood were ripe for deconstruction.

23. Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971) — As my friend said after watching Wake in Fright, “it’s a horror movie about being a man.” A schoolteacher (Gary Bond) in the tiny outback town of Tiboonda is about to head home to Sydney for the holidays, but he’s waylaid in the even tinier town of Bundanyabba, where a group of rowdy local men entrap him in their games of alcoholic debauchery, hunting kangaroos, homoerotic desire, and generally unleashing their pent-up rage. It’s not an easy watch, but it’s a provocative and (dare I say) important depiction of masculinity’s worst, most implosive attributes.

24. Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindō, 1968) — One of my favorite Japanese New Wave horror movies is a grim fable about a woman and her mother-in-law, abandoned by their husband/son, who are raped and killed by a group of samurai, only to return as ghostly black cats. It’s a horrific revenge story that becomes complicated when the husband/son returns, pitting him against the women he used to love. Like many Japanese New Wave movies, Kuroneko crafts an eerily beautiful atmosphere, with vivid cinematography by Kiyomi Kuroda and haunting music by Hikaru Hayashi.

25. Miami Vice (Michael Mann, 2006) — Am I revealing my love for Michael Mann too blatantly? Manhunter and Miami Vice are my two favorites by him, with the latter counting as one of the most visually striking and audacious films of the 21st century (no wonder Steven Hyden called it “one of the most expensive art films ever made”). The one-of-a-kind digital cinematography would be enough to warrant acclaim on its own—I could watch the movie’s scenes of speedboats, jet planes, and pyrotechnic gunfire for hours on end—but there is real pathos in the doomed relationship between Colin Farrell and Gong Li’s characters. Their chemistry is one of many surprises Miami Vice has to offer.

26. The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953) — At barely more than an hour long, The Hitch-Hiker is one of my favorite low-budget Hollywood thrillers; it’s often called a film noir, but I think it’s closer to a male melodrama, as it really focuses on the terse friendship between middle-aged Roy (Edmond O’Brien) and Gilbert (Frank Lovejoy). My full thoughts on The Hitch-Hiker can be found here.

27. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (Radu Jude, 2024) — My favorite movie of this year is the newest from Romanian provocateur Radu Jude, who’s one of the few global filmmakers right now whose work could accurately be called Marxist. DNETMFTEOTW follows Angela (Ilinca Manolache), a video producer who drives around Bucharest recording short segments about workplace safety on behalf of a multinational corporation. In her free time, she poses as an Andrew Tate-style incel on social media, recording vulgar diatribes about men’s rights and the meaning of masculinity. In a just world, Manolache would be celebrated during awards season for her fiery, committed performance, but this isn’t really the kind of movie that’s aiming for awards—its target instead is our current late-capitalism era, which is as foreboding as this movie’s title suggests.

28. The Golden Coach (Jean Renoir, 1952) — This is one of three French-Italian movies that Renoir made about art, love, and sex in the 1950s with celebrated actresses: Anna Magnani in this case, Françoise Arnoul in 1955’s French Cancan, and Ingrid Bergman in 1956’s Elena and Her Men. The latter is my favorite of the three, but The Golden Coach is almost as radiant. Magnani plays an actress in a commedia dell’arte troupe, performing in Peru in the 1700s; she’s fought over by various men in the town but is ultimately committed to her art (at least until a late crisis of conscience breaks through). As a love letter to theater, cinema, and Magnani, The Golden Coach is a resplendent highlight in Renoir’s fascinating later period.

29. Canoa: A Shameful Memory (Felipe Cazals, 1976) — Based on the San Miguel Canoa tragedy of 1968—in which five young university employees were lynched after a conservative priest convinced the townspeople that the young travelers were Communist agitators—Canoa: A Shameful Memory reflects the social unrest that persisted in Mexico well into the 1970s. While I don’t always find the movie’s documentary-style interviews convincing, it still builds to inevitable violence in grueling, unsettling fashion. One shot—an image of the power-hungry priest standing in front of a flaming church—is truly an image for the ages.

30. Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956) — Two years before he made Some Came Running (see above), Minnelli made another ravishing melodrama focusing on themes of masculinity and repressed sexuality. Tea and Sympathy stars John Kerr as Tom, a student at an all-male boarding school who fails to act in the ways his über-masculine peers expect him to: his hair is long, he enjoys sewing and poetry, he buys curtains to decorate his dorm room windows. This ostracism leads to several shocking outcomes, especially after Tom starts a (possibly sexual) friendship with an older woman, the school’s headmistress (Deborah Kerr). With astounding color compositions and sensitive performances creating complex characters, Tea and Sympathy is yet another classic to add to Minnelli’s résumé.

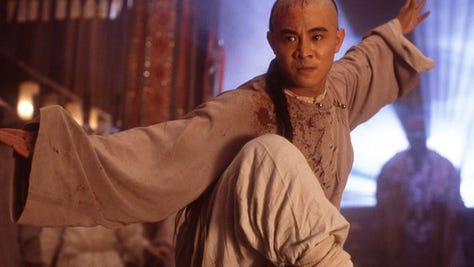

31. Once Upon a Time in China II (Tsui Hark, 1992) — The Once Upon a Time in China movies are my favorite action franchise of all time, with the charismatic presence and incredible kung-fu skills of Jet Li paired with Tsui Hark’s visual dynamism and Yuen Woo-ping’s electrifying fight choreography. The second film is my favorite in the series, with a propulsive plot that includes a xenophobic religious sect, an impending rebellion, an ultraviolent military commander, and an array of foreign nations battling for supremacy in Canton. The rare sequel that improves upon the original, OUATIC II is breathlessly exciting from first frame to last.

32. Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (Nagisa Ōshima, 1983) — Japanese director Nagisa Ōshima could always be relied upon to push against restrictive social conventions. In its own way, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is as audacious as Ōshima’s infamous 1976 film In the Realm of the Senses, offering a queer-themed update of Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937). Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence stars Ryuichi Sakamoto (who also composed the dreamy music) as Captain Yonoi, who rules over a Japanese POW camp in Java in 1942. A strong-willed British prisoner (David Bowie) awakens Yonoi’s homosexual urges, which he’s forced to suppress as a Japanese commander. Even if his English dialogue isn’t always convincing, Sakamoto is a forceful presence as Yonoi, and the film painfully empathizes with his inability to be the man he truly is due to the rigid demands of conservative society.

33. Casque d’Or (Jacques Becker, 1952) — Crime story set during the Belle Époque depicts the doomed love affair between a beautiful gangster’s moll (Simone Signoret, whose blond hair represents the “golden helmet” of the title) and a handsome carpenter (Serge Reggiani) just released from prison. The story itself is a fairly predictable tale of passion and murder, but its real pleasures are non-narrative: Signoret’s performance, Becker’s convincing depiction of turn-of-the-century Paris, a sense of erotic liberation, and a justly celebrated final scene.

34. Nightfall (Jacques Tourneur, 1956) — Tourneur made so many great movies that some of his best are undervalued—particularly this touching quasi-film noir made on the cheap for Columbia. Aldo Ray is an unusually tender leading man as Jim Vanning, who’s hunted by bank robbers (and a bank insurance investigator) after he steals the loot from a recent heist. When Jim encounters a similarly desperate fashion model named Marie (Anne Bancroft), they team up to outwit the criminals. Nightfall has the distinction of being a great “city movie”—its urban locale is moody and mysterious—while also setting its flashbacks and climax in the wintry great outdoors, with Burnett Guffey’s beautiful cinematography capturing the essence of both worlds.

35. Heat (Michael Mann, 1995) — It’s a Michael Mann hat trick: his classic 1995 actioner Heat is another homage to Jean-Pierre Melville, depicting cops and robbers as flip sides of the same coin, going about their business with (somewhat arbitrary) codes of honor and justice. Heat has a little more formula (and therefore less personality) than the other Mann titles on this list, but its action scenes are practically flawless, and the clash of Pacino and De Niro is as titanic as it should be.

36. Sidewalk Stories (Charles Lane, 1989) — It’s too bad Charles Lane didn’t make more movies: he has only a few features on his filmography, but one of them is this remarkable (almost) silent comedy that pays tribute to Chaplin (and Keaton, Lloyd, et al.) while recognizing the huge gap between real-world and cinematic poverty. The film references The Kid (1921) explicitly in its story of a street artist (Lane) who cares for a young girl whose father is killed on the street. Lane’s penchant for silent comedy and staging makes for a rewarding and entertaining watch, though the film really comes alive in its final scene, in which Lane’s subversive intention becomes clear.

37. Border Incident (Anthony Mann, 1949) — Like Mann’s 1947 film T-Men, Border Incident infuses the noir-thriller prototype with hot-button social issues—in this case, illegal immigration and crime networks proliferating along the US-Mexico border. Despite the image of sinister Mexicans above, Border Incident is careful to emphasize that most Mexican immigrants come to the US legally, and the real villains are the American crooks and politicians who exploit them. Ricardo Montalban is excellent as a Mexican officer who teams up with an American agent, but the real star here is John Alcott’s cinematography, which somehow makes wide-open desert expanses feel like shadowy, claustrophobic sites of danger.

38. Within Our Gates (Oscar Micheaux, 1920) — Micheaux was the most influential Black director of the silent era, writing, directing, and producing his own work that catered specifically to Black audiences and countered the negative stereotypes so prevalent in American film at the time. Within Our Gates was an emphatic response to The Birth of a Nation, portraying an inverse storyline that was closer to historical reality: the threats of violence and sexual assault posed to African Americans by Southern whites. Sure, Within Our Gates has some clunky storytelling (including a late plot twist revealed entirely through an intertitle), but its explosive depictions of racial violence, religious hypocrisy, and miscegenation make up for that.

39. The Boys from Fengkuei (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1983) — After three semi-mainstream comedies kickstarted his career, Hou turned to the slow-paced, enigmatic, austere style that would define his later films with The Boys from Fengkuei. A major influence on the burgeoning Taiwan New Cinema, the film concerns a group of boisterous young men who feel trapped in their titular hometown and unleash their pent-up aggression any way they can. As in many of Hou’s later films, the underlying emotional currents are so subdued that you hardly notice them until they strike in full force—which The Boys from Fengkuei accomplishes through innovative use of flashbacks. The best scene depicts the boys being lured to an upper floor of an unbuilt skyscraper with the promise of a peep show—but once there, they realize they’ve been duped and there’s nothing but the skyline of Kaohsiung, an attraction in its own right.

40. Bona (Lino Brocka, 1980) — Five years after releasing the now-classic Manila in the Claws of Light, Lino Brocka made the indescribable comedy-drama Bona, which tackles similar subject matter through an almost farcical tone. Nora Aunor is powerful in the titular role, a young woman who experiences a dismal family life (abusive father, angry brothers, long-suffering mother and sisters) and forcibly moves in with Gardo (Phillip Salvador), a shallow playboy, even though he treats her like shit. Why would Bona subject herself to Gardo’s cruelty when she has the chance to be in happier relationships with kinder men? The audience must glean how patriarchy and the lack of opportunity have affected her over the years. It all leads to a climax that’s both disturbing and crowd-pleasing, which could describe this remarkable Filipino movie as a whole.

41. Angst (Gerald Kargl, 1983) — “Horror” doesn’t begin to describe the impact of this massively disturbing serial killer portrait, which plants the viewer deep inside the nauseating mind of a homicidal maniac. Director Gerald Kargl and cinematographer Zbigniew Rybczyński wield an array of dollies, cranes, and other equipment to create a sickening, dazzling aesthetic: we crawl, swoop, and hover right next to the violent action, which only makes things more unsettling. (No wonder Gaspar Noé is a fan.) In the end, we may not learn much about what compels someone to kill, but there’s no forgetting the nightmarish mania on display.

42. Insignificance (Nicolas Roeg, 1985) — In anyone else’s hands, this adaptation of Terry Johnson’s stage play might have been cringe-worthy: Marilyn Monroe, Albert Einstein, Joe DiMaggio, and Joseph McCarthy meet up in a New York hotel one night in 1954, offering a powder-keg microcosm of American life in the mid-’50s. In Nicolas Roeg’s hands, this becomes an exhilarating formal experiment, boasting a sincere performance by Theresa Russell. A jaw-dropping climactic montage says more about nuclear annihilation in about five minutes than Oppenheimer did in its entire runtime.

43. The White Balloon (Jafar Panahi, 1995) — Panahi’s feature debut—written by his mentor, Abbas Kiarostami—follows a young girl in Tehran who convinces her mother to give her money so she can buy a goldfish, though she promptly loses the money and needs to rely on the help of fellow Tehranians to get it back. This sounds like pleasant, charming fare, which it is in some ways, though it’s also surprisingly grim as it focuses on Iran’s patriarchal culture and distrust of foreigners, particularly Afghans. When placed alongside Kiarostami’s own Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987), which has similar subject matter, The White Balloon pales in comparison; when viewed on its own terms, though, Panahi’s film is a highly affecting social drama and an auspicious debut for one of modern cinema’s best directors.

44. The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) — Classic heist caper stars Sterling Hayden—one of the only Hollywood actors who could believably play a hardened criminal—as Dix Handley, who’s enlisted in a jewel robbery that inevitably goes awry. Along with Harold Rosson’s starkly beautiful cinematography, this is a film enlivened by its cast: not only Hayden, but also Sam Jaffe as career criminal “Doc” Riedenschneider and Jean Hagen as Dix’s long-suffering moll.

45. The Straight Story (David Lynch, 1999) — As a quiet, ruminative family drama, The Straight Story is simultaneously an unusual project for Lynch (nothing overtly surreal happens) and an ideal expression of his “life is strange” worldview. Richard Farnsworth, in his final role (stricken with cancer, he died less than a year after the movie premiered), stars as Alvin Straight, a 73-year-old Iowan who journeys to Mount Zion, Wisconsin, via tractor to visit his ailing brother, with whom he had a falling out years earlier. The regrets, pains, hopes, and fleeting joys of an anonymous life are the real subject here, which are heartbreakingly conveyed through the movie’s wistful tone. Somewhat episodic in nature, The Straight Story’s life lessons can feel sentimental at times, but even that’s somewhat admirable as an expression of the unpredictable and sometimes melancholy paths that life can take.

46. Ishtar (Elaine May, 1987) — I’m on board for the critical reappraisal of Ishtar, which, like many of Elaine May’s movies, seemed to get a raw deal in their production and critical reception. Maybe this was the last gasp of a New Hollywood that had already been fully supplanted by the blockbuster likes of Jaws, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, etc. As an absurdist political comedy with a massive budget, shot on location in Morocco by Vittorio Storaro, Ishtar was probably doomed to failure, but it holds up as a smart and hilarious parody of American buffoonery and oblivious artists: Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman are laugh-out-loud funny as lounge singers who find themselves in over their heads in a fictional country mired in revolution. It’s not perfect, but I would argue it’s something even better: fascinatingly imperfect.

47. Light Sleeper (Paul Schrader, 1992) — This isn’t the time or place for candid confession, but the plot of Light Sleeper—a forty-year-old drug dealer (Willem Dafoe) faces a personal and professional crossroads, desperate to fix the mistakes of his life before it’s too late—hit uncomfortably close to home for me on this rewatch, in the midst of an extremely difficult year. The possibility of transcendence and the need for (and impossibility of) self-forgiveness are thematic motifs throughout Paul Schrader’s career, and they receive some of their fullest expression in Light Sleeper, one of the best American movies of the early ‘90s. I would do anything to give this movie a different soundtrack, and maybe some of the symbolic imagery of saints and martyrs is a little too on-point, but it doesn’t matter: this is humanist, sophisticated drama that refuses to shy away from life’s more uncomfortable questions.

48. Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948) — John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, Howard Hawks, the wide-open expanses of the American southwest in sparkling black-and-white . . . what’s not to love? An overfamiliar plot, perhaps (screenwriter Borden Chase admitted it was Mutiny on the Bounty with saddles and stirrups), and a cop-out ending that defuses all the compelling drama that came before it. Still, this is Wayne’s first complex performance, and the surrogate father-son relationship between him and Clift remains poignant.

49. For Your Eyes Only (John Glen, 1981) — My favorite thing about For Your Eyes Only, Roger Moore’s fifth outing as James Bond, is Robert Bresson’s love for it: he said it filled him with wonder and “if I could have seen it twice in a row and again the next day, I would have done.” That’s both surprising and completely understandable: it’s my second-favorite 007 picture (after On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), filled with globetrotting scenery, exhilarating action, and a tight, well-crafted aesthetic. At its best, this harkens back to the thrilling adventure serials of the silent era. How can I not show love to one of my favorite installments of a series that transfixed me as a boy and continues to carry nostalgic value?

50. Megalopolis (Francis Ford Coppola, 2024) — To anyone saying this is one of the worst movies of the year, or even one of the worst movies ever, I beg you to reconsider what you find valuable about movies in the first place. Yes, it’s uneven and messy, occasionally preposterous, embarrassingly earnest. It’s also one of the only times I’ve spent in a movie theater recently that has felt alive, significant, electrifying. I don’t love most of Coppola’s recent output, but here is a die-hard artist who, late in life, spent most of his personal fortune on a wildly ambitious, unabashedly personal comment on where America is at in 2024.

Notes

Number 51 would be Popeye, Robert Altman’s divisive comic-book adaptation. I swear I’m not always on board with overzealous critical reappraisals, but I think they apply to both Popeye and Ishtar. As a friend commented after watching Popeye, this seems like Altman’s version of populist entertainment, and inevitably it’s as weird as hell, with a Tati-like plurality onscreen that allows the viewer to focus on whatever they want.

Number 52 is my third-favorite film of 2024: Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast. I’ve loved Bonello since House of Pleasures (2011) and particularly admire Nocturama (2016). Like most of his work, The Beast can be frustratingly obtuse, but therein lies the mystery and significance: in its freewheeling commentary on identity, technology, love, and labor in the digital age, The Beast feels significant, and I think people will return to it over the years to continue decoding its enigmas.

A Personal Postscript

Above I alluded to an incredibly difficult year that I experienced in 2024. I won’t go into much greater detail here, but this was a year in which I confronted personal, professional, and political hardships like never before. As I’ve tried to claw my way out of this experience, there have been many balms on the wound: friends, family, therapy, creativity, exercise, and so on. But, as always, movies are one of my foremost pleasures, and I need to shout out two unlikely candidates (and the friends who were present for these screenings).

Two days after the most intense heartbreak I’ve ever known, I went to a friend’s house in Minneapolis, who offered his couch for me to sleep on for a day or two. Obviously we decided to watch a movie, and something relatively mindless and entertaining was the wisest choice. The selection: Jean-Claude Van Damme in Maximum Risk (1996), directed by Hong Kong action maestro Ringo Lam. I love Van Damme even though many of his movies are terrible: aside from Jackie Chan and maybe Jet Li, I don’t know if there’s ever been a more charismatic action star.

Maximum Risk is one of the many Van Damme vehicles that feature identical twins whose lives take divergent paths. In this case, one Van Damme is a Russian gangster, the other is a French detective. (It barely makes any more sense when you watch the movie.) Maximum Risk opens with a thrilling foot chase through Nice, France, and later features an incredible fight scene in a burning building. Van Damme’s line delivery is as charmingly stilted as always, and the plot is tight and quickly paced, hitting all the satisfying action-movie paces.

Is it a great or even a good movie? Who fucking cares? As I sat on my friend’s couch that night, after a few beers and perhaps a few edibles, it seemed like the best film ever made, tailor-made for my particular and unfortunate situation. Before and after the film, my friend and I talked about loss, grief, regret, heartache, those personal tragedies that most people experience at one time or another. I am infinitely grateful to him for those conversations. And I’m also infinitely grateful to Maximum Risk, which I will never forget for that reason.

A few weeks later, with another friend, I watched Martin Scorsese’s 1991 remake of Cape Fear. This friend, too, had supported and listened to me through this extremely difficult period, providing compassion and a listening ear. He expressed optimism that I would find happiness going forward. Step one in that process was rewatching Cape Fear, in which Robert De Niro devours the scenery as Max Cady, Scorsese incorporates every visual and editing trick he can possibly think of, and composer Elmer Bernstein does his best Bernard Herrmann impression. Scorsese has many better movies than Cape Fear, but are any of them more entertaining? Are any of them as wildly, blissfully diverting? Do any of them provide the same level of cinematic adrenaline, divorced from ideas of quality or good taste? After rewatching it in July 2024, I would answer emphatically no.

So here’s to the friends and family members you watch movies with, particularly during the most trying times when all you want is to step outside your brain for a little while. And here’s to the movies themselves, which make it thunderingly obvious how important entertainment and escapism can be. I think, years from now, I’ll look back on this time as a low point I’ve suffered through, finding a new path on the other side. The people will be the most important part of that recollection—the people I love, who provided vital support and understanding I can’t begin to repay. But the movies will be almost as important, and I know in the future I’ll look back on Maximum Risk and Cape Fear as the films that lifted my spirits through the depths of heartache, that made me smile, that reminded me why I love movies in the first place.