The Phoenician Scheme

Wes Anderson returns to the well, and this time around that's mostly a good thing.

I haven’t been shy about my dislike for Wes Anderson in recent years; his last movie I really loved was The Grand Budapest Hotel way back in 2014, and ever since then it’s hard to deny that he's fallen into a trap of self-repetition. Asteroid City supposedly comments on the minor and major tragedies of human life, but mostly it goes to show how out-of-touch Anderson is with most people’s lived experience. The French Dispatch has absolutely nothing to say about any of its supposed subjects, though at least its omnibus style allows for some creativity and a looser kind of storytelling. Isle of Dogs opts for tired deadpan humor over pointed social commentary, with its critique of despots and tyrants couched inside some lame cultural exoticism. Of course every artist has the right to build a distinct world and return to pet themes and styles, but there’s a difference between an authorial stamp and self-regurgitation, and Anderson too often falls in the latter category.

So the following review for The Phoenician Scheme is actually something of a rave in my book; this is perfectly enjoyable, with some substance beneath the overt Anderson touches. It could have been even better if Anderson didn’t stick to his branding so much, but there’s a lot of pleasure to be found in the director’s immaculate dioramas this time around. Maybe, after decades of similar movies, I don’t have the energy to either adulate or lambaste Anderson anymore.

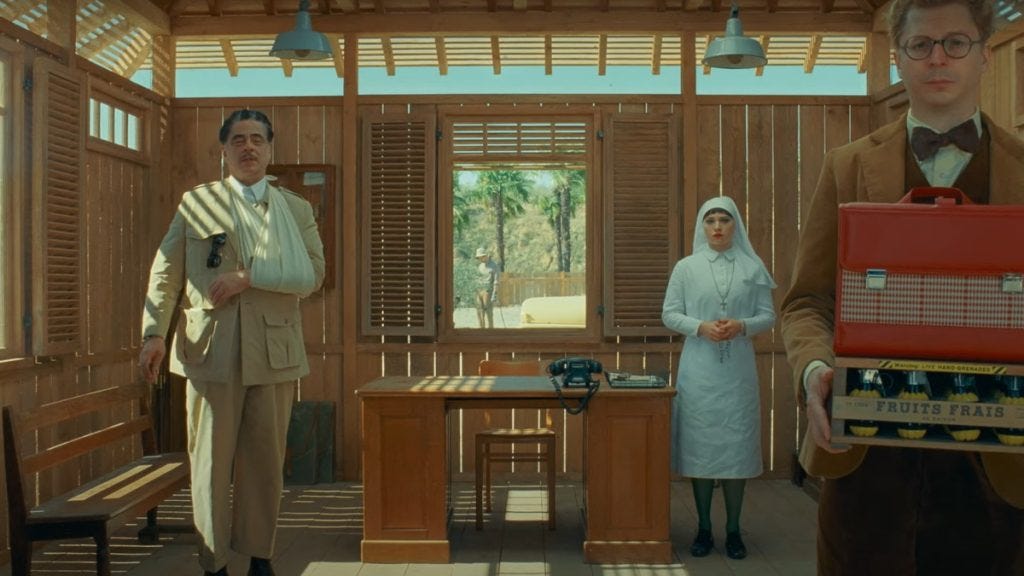

Benicio del Toro plays Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda, a rich and powerful business magnate in the fictional titular country (which, a map shows us, is vaguely around the Middle East) circa 1950. Targeted by world governments and assassins, Zsa-Zsa is briefly killed by his most recent murder attempt, sending him to Heaven to face divine judgment. Sent back to Earth (it’s not yet his time to move on), Korda finds new motivation to reconnect with his daughter Liesl (one of his many kids with numerous wives and lovers); she’s a nun in a Catholic convent, where she’s been since the age of five (at Korda’s behest, following the death of her mother). Meanwhile, as Zsa-Zsa and Liesl take hesitant steps to become a real father and daughter, he attempts an ambitious takeover of Phoenicia’s infrastructure that will make him and his partners rich for the next 150 years. (No matter, at least for Korda, that this scheme depends on the use of slave labor, though he constantly and shamelessly insists that his slaves will receive a “stipend.”)

The business partners that Korda lines up showcase a who’s-who of revered actors, as most of Anderson's movies now do, given his unmatched clout as a director. Riz Ahmed, Bryan Cranston, Tom Hanks, Mathieu Amalric, Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, and Benedict Cumberbatch all show up as Zsa-Zsa’s untrustworthy associates; other supporting roles are filled by the likes of Richard Ayoade, Bill Murray, Willem Dafoe, etc. This is both a pleasure and a detractor. These are all charismatic actors who are offered amusing comedic touches (love the game of old-school basketball played by Hanks and Cranston), but many of them do next to nothing in only a few minutes (even seconds!) of screen time. Imagine if Ayoade’s Communist revolutionary was an actual role instead of a quirky cameo (which seems to come straight out of one of the plays in Rushmore or The French Dispatch), or if we knew anything at all about Johansson’s character (Korda’s cousin), or if del Toro and Charlotte Gainsbourg (who makes a brief appearance as his murdered wife in Heaven) had an interaction that reflected their history as lovers and occasional enemies. I realize this would have made for a long movie, but it also probably would have been a better one; Anderson is more concerned with trotting out his ensemble of A-list friends than giving most of them something substantial to work with.

All those unexplored characters and subplots are especially unfortunate because The Phoenician Scheme has so much rich potential. Beneath all the bright and fanciful visuals is, surprisingly, a theme about morality, goodness, and religion. On the surface, Zsa-Zsa is a repugnant character: he’s made his fortune by lying, cheating, and stealing, a little too comfortable with violence if it helps him achieve his business ends. His former wife, Liesl’s mother, took numerous lovers while they were married—there’s even the question of who Liesl's father actually is. His business partners, meanwhile, are similarly unscrupulous; Johansson’s character admits she's marrying Korda as a lark, but it won't pressure her to invest any more money in his Phoenician scheme.

“Sister Liesl” would seem to be a contrast to all this amorality: a novitiate since the age of five, she’s committed to a life of God and seclusion, at least until Zsa-Zsa plucks her out of it. He professes surprise that she stayed in the convent so long: he put her there as a child only to shield her from the attention of boys but never expected her to take religion seriously. Even her own Mother Superior tells Liesl that the monastic life is not for everyone and someone like Liesl might be more fulfilled by a life outside its walls. Liesl quickly realizes that the chaste, celibate life of a nun does not necessarily lead to goodness and purity, and a life of hedonistic pleasure doesn’t necessarily lead to damnation. There’s a funny running joke in which Liesl is offered alcohol by numerous men: she always demurs at first, saying nuns don’t drink hard liquor, but then eagerly tries everything she’s offered after barely any hand-wringing. (Echoes of Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story!)

In short, Liesl realizes that religious piety is not shorthand for goodness, and that her father may in fact be a marvelous human being despite his endless list of crimes and betrayals. That theme sounds trite, maybe, but Anderson’s light touch does actually make it feel well-earned and agreeable, if not very emotional (probably another negative side effect of the constant tone of irreverence). All this questioning of morality, goodness, and so on reminded me of Lubitsch, whose pre-Code comedies were filled with love affairs, adultery, unbridled lust, etc., but it was obvious his characters were essentially good people who did the wrong things for understandably human reasons. (The fake kingdom of Phoenicia also recalls some of the fictional countries in Lubitsch films, like Sylvania in The Love Parade.)

One way this theme falls short, though, is in the movie’s portrayal of Heaven. This world is strikingly presented in sharp black-and-white, with spectacular sets and austere costumes reminiscent of both A Matter of Life and Death and Ivan the Terrible. But not much of consequence happens in Heaven: the brief, jokey dialogues make sure this potentially fascinating setting doesn’t lead to any interesting comments on spirituality or the afterlife. (This is especially disappointing when you have Bill Murray playing God and Willem Dafoe playing a divine interlocutor.) If The Phoenician Scheme had slowed down during these moments and tried to seriously question the meaning of Heaven—in other words, if Anderson had stepped outside his comfort zone—the movie could have really been profound, a comedy that dares to tackle the biggest themes of human existence. But Heaven here is mostly just another of Anderson’s shoeboxes, arranged for his amusement primarily, the audience’s amusement secondarily.

For better or worse, most of the film's powerful comments on goodness and morality take place on Earth. My favorite moment arrives when Liesl (already on the verge of quitting the convent) admits she has never heard God speak to her during her prayers. So she just behaves the way she thinks God would tell her to anyway, and it usually works out alright. Zsa-Zsa gives his daughter a loving look, perhaps realizing that what she's just described is how most people go through life (religious or not), and in a single word delivers The Phoenician Scheme’s most moving, profound, and memorable dialogue: “Amen.”