The postwar years occasioned for Alfred Hitchcock a desire to experiment formally and plumb the darker side of human nature. Films like Notorious (1946) explore the uglier aspects of humanity, whether it comes to personal relationships or social and political forces; the sense of moral decay in that movie is overwhelmed by the shadow of World War II. Meanwhile, movies like Lifeboat (which came out in 1944, as the war still raged) and Spellbound (1945) take bold aesthetic chances, like radically confined sets and overtly surrealist sequences. With the exception of Notorious, this period (which also includes The Paradine Case [1947] and Under Capricorn [1949]) isn't generally considered Hitchcock's finest, but I think it might be his most interesting—and one movie from this era, Rope (1948), deserves to be considered among Hitchcock's best.

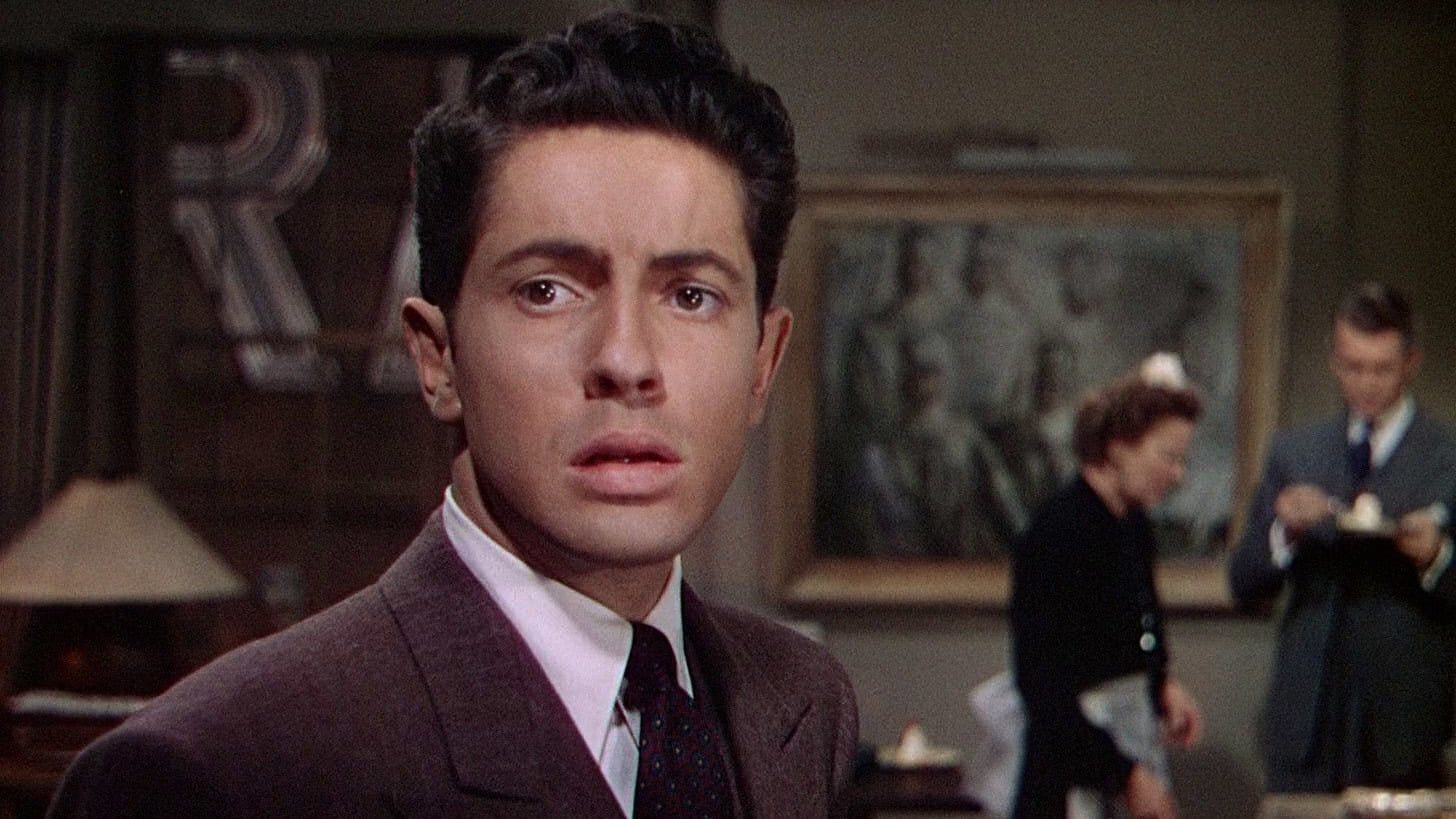

The stylistic conceit of Rope is well-known: it consists only of 11 long takes, several of which last about ten minutes (the most a camera's film canister could achieve at that time). Most of the transitions from one shot to the next are "hidden cuts" (i.e., a pan across a dark piece of clothing allows for a new, but seemingly unbroken, shot), but there are a few undisguised edits, which land with unexpected force. In the midst of this formal experimentation is a morbid story about two killers, Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger), who strangle one of their friends and hide his corpse in a chest during a dinner party to see if they can get away with it.1 One of the party's guests is their former professor, Rupert (James Stewart), who often pontificated in class about whether murder is an innately immoral act and what kind of Übermensch it would take to actually commit the deed.

Hitchcock loved gruesome jokes and sensational scandals about grotesque killings; Rope almost seems like an amusing anecdote he might tell at one of his own dinner parties (though it was actually based on a 1929 play). The vigor with which Rupert and Brandon debate the specifics and ethics of murder—and the obvious delight the other party guests take in this discussion—recall similar moments in Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Strangers on a Train (1951). But the aftermath of WWII casts a more tragic shadow on the prevalence of death in Rope (not to mention the fact that the victim's father is one of the oblivious guests). Brandon may feel that murder is a minor thing, since governments are willing to inflict it upon their own citizens without a second thought (a point that Chaplin also emphasized in Monsieur Verdoux, which came out a year before Rope); but, as Rupert tells Brandon near the end (in an overly clunky and didactic speech), there's a difference between philosophizing about a heinous act and actually committing it.

In fact, the distance between theory and action is a surprisingly insistent theme in Rope. Freud and Nietzsche are blatantly name-dropped in the movie: Brandon admiringly cites Nietzsche's theory of the superman, while Freudian psychoanalysis is mentioned numerous times as a way to decode the subconscious thoughts behind our actions. Obviously those two figures dominated early twentieth century thought, in ways that are inextricable from World War II: Hitler and many other Nazis fashioned themselves supermen (as most fascists and tyrants do, right up to Trump), and Freud sought to dissect the sometimes destructive impulses at the core of human thought and action, which received their horrific epitome in the Holocaust. These overt references to Freud and Nietzsche reflect the unease and uncertainty of the early twentieth century and the sense of moral alienation after the war, making the film's experiment in murder much more than just a macabre gimmick.

Not surprisingly, Rope's distinct aesthetic is bold and striking. The exact staging and choreography of the camera and actors is immaculate, subtly shifting perspective to highlight characters and objects lurking on the fringes of the screen. Hitchcock was a longtime lover of the theater, and Rope gives the impression of a theatrical audience that’s somehow allowed to intrude upon the stage, viewing the actors, props, and sets with disconcerting intimacy. This is one case where a theatrical effect is achieved cinematically for a specific, powerful purpose, as the real-time duration of the long takes builds suspense by making us wonder when someone’s going to discover that corpse.

Even aside from the long-take approach, though, I forgot how weird and adventurous Rope is. In one scene, the camera adopts Rupert's phantom POV as he envisions how he would commit the murder himself: the camera floats around the set, suggesting a killer and victim who are absent from the frame, and the moment feels alive and unexpected in ways that few American movies could achieve at the time, at least stylistically. Later, after Rupert has discovered Brandon and Phillip's crime, the garish red-and-green lighting visualizes the characters' growing fear and disgust in ways that foreshadow the opulent lighting of Vertigo (credit must be given to the Technicolor cinematography, which makes the formal bravado even more impressive).2 The theatrical set and backdrop, meanwhile, look forward to the dazzling world of Rear Window. It's no bold claim to say that Hitchcock was a peerless visual stylist, but Rope offers some of the most unique and convincing evidence.

When it was released, Rope didn't do very well commercially (or critically), with some even questioning whether Hitchcock was on the downswing. It's not perfect: James Stewart is miscast as the nihilistic philosophy professor, though it's interesting to consider that Stewart was still getting back into a life of acting after the war and dealing with his own PTSD.3 (Stewart's truly dark performances were a few years off, but some of his line readings here are unforgettably vicious, like the revolted way he tells Brandon, "You've murdered!!") I could also see someone preferring the more opulent visuals of Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, etc. Still, Rope is a fascinating, exhilarating outlier in both American cinema and Hitchcock's filmography, stuffed with visual and philosophical ideas that perfectly reflect the anxiety of the late 1940s. It might not be my favorite Hitchcock, but after this rewatch, it's the one I want to champion most vehemently.

The fact that the two killers, Brandon and Phillip, are strongly implied to be gay is almost tangential. I could see someone taking issue with this representation, though it seems mostly a result of the fact that the two characters are based on Leopold and Loeb. Furthermore, it adds a sympathetic shade to the Phillip character, who mostly seems to be going along with this deadly stunt to impress his lover.

Much is made in the Hitchcock biography A Life in Darkness and Light by Patrick McGilligan of the logistical difficulties involved in the production, which would grow even more arduous in Hitchcock’s next production, Under Capricorn (which also used a long-take technique). Stewart in Rope and Ingrid Bergman in Under Capricorn both complained about how strenuous the shoots were, as the actors and technicians had to be flawless in achieving these long takes. The fact that Hitchcock and his Rope cinematographers, Joseph A. Valentine and William V. Skall, made things even more complicated by shooting in Technicolor shows how Hitchcock entrenched his growing power in Hollywood to combine top-notch resources with formal experimentation.

The role might have been better suited for Gregory Peck, who had recently worked with Hitchcock on Spellbound (1945) and The Paradine Case (1947).